There’s a quote I’m fond of, falsely attributed to Lenin, that “ethics are the aesthetics of the future.” It was in fact coined by Gorky, and as with so many misattributed phrases, it is also misquoted. I had always quietly reordered the line in my mind, preferring to have aesthetics in the first position, and when I finally went looking for it, and found it — in an essay Gorky wrote on Anatoly France — I was vindicated to discover that it actually read: “Aesthetics was [his] ethics — the ethics of the future.” That it’s thought to be authored by Lenin is perhaps understandable: it is a revolutionary sentiment after all, one that would have pleased the Romantics, the Surrealists, or any other radical avant-garde that aimed at transvaluation. It could also easily be, I think, the unofficial epigraph, the spiritual motto of Peter Weiss’s trilogy of novels, The Aesthetics of Resistance.

Published in German between 1975 and 1981, The Aesthetics of Resistance has only recently come to the attention of English readers. The first volume was translated and published by Duke University Press in 2005, followed by a long lag, with the second volume not published until 2020, and now the final volume published this year. Notoriety for the novel has risen in recent years, and though it has surely been added to plenty of to-do lists, it is likely to remain a distant ambition for many readers, a hike they will pledge to one day undertake, partly due to its formal challenges, its great length (tallying nearly 900 pages), the density of its material, and not least its internecine ideological harangues. Indeed, Weiss himself once described the book as a hike — or to be exact, a Hades-wanderung, a Hades-hike.

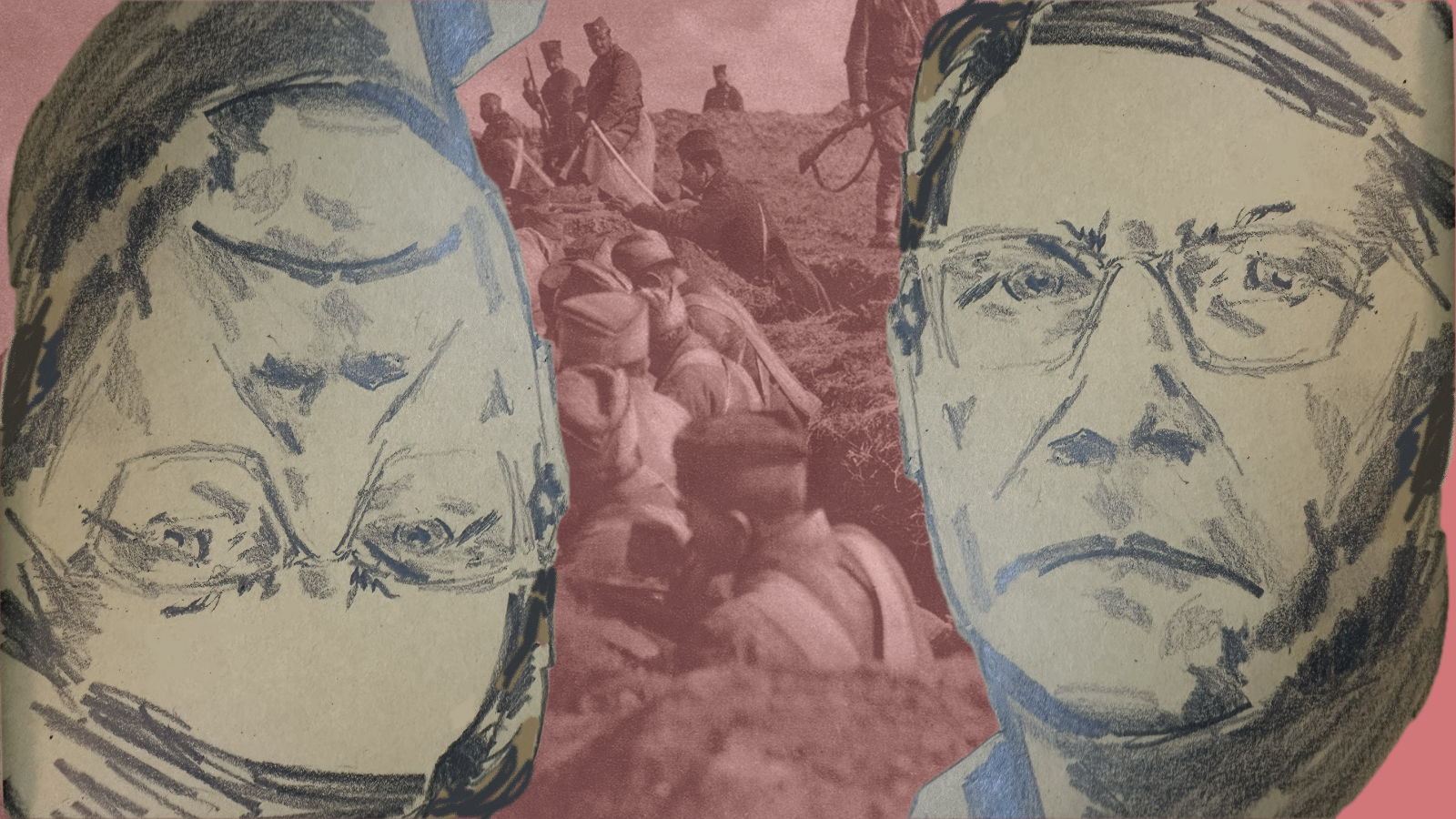

These are dark times, and Weiss’s novel is about the darkest of times, between 1937-1942, roughly — a period that Victor Serge dubbed the “midnight in the century.” The novel is a horrific panorama, a triptych of disaster, reminiscent of Breughel, by whom Weiss (also a painter early in his life) was greatly influenced. From the outset, one calamity accompanies another: the Nuremberg Laws, the left’s defeat in the Spanish Civil War, the Anschluss, Kristallnacht, the annexation of Czechoslovakia, the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, the fall of France, the assassination of Trotsky, and so on — as the narrator, his family and his friends flee Nazism’s cancerous takeover of the continent. It is well-worn territory for the left: the pangs of historical memory, betrayal, disillusionment, the revisitation of defeats, of missed or failed revolutionary moments, the melancholy recall of wrong decisions and old divisions. The novel is a political and ideological history, a work of aesthetic theory, a eulogy, but it also represents Weiss’ attempt to derive a coherent vision and understanding of his own politics from a lifetime of experience. It contains ekphrastic meditations on works of art, dialogues about party politics and thorough goings-over of contemporary events. It is written in long, unbroken paragraphs — solid walls of text, not unlike a frieze — and although it is narrated in the first-person, it contains a chorus of voices that gives it a dialogical resonance — its monological interiority shifting to scenes, places, times that the narrator doesn’t in fact inhabit, a riverine, dream-like quality has been described as surrealist, or “hallucinatory realism” (in Burkhardt Lindner’s words).

The novel represents, as the narrator says at one point of The Divine Comedy, “an epoch concentrated into a subjective vision.” Dante is very much the presiding influence here. Weiss was increasingly obsessed with the Comedia throughout his life and his trilogy aspires to the same level of epic, as an autobiography, a memorialization of the dead, a condemnation of the wicked, a record of the crimes of the time, and a longing for a redress that its author knows is impossible. Like Dante, Weiss wrote his work in a state of exile (having lived in Sweden since 1938) and found in aesthetic expression an act of resistance against worldly injustice, and like Dante’s infernal circles, in Weiss’s novel, that which might seem like a nightmare is actually the inhabited world.

The Aesthetics of Resistance is ultimately a bildungsroman, but it is a proletarian bildungsroman, an attempt to disentangle the genre from its bourgeois origins. Weiss was writing slightly outside of his class. He was petit-bourgeois and Jewish, whereas his narrator is proletarian and gentile. Nearly all the characters in the novel are real historical figures (Max Hodann, Karin Boye, Rosalinde Ossietzky, Bertolt Brecht, Charlotte Bischoff) with the exception of the narrator and his parents, though they bear resemblance to Weiss and his own family: he was born in Bremen in 1916, which would have made him roughly the same age as his narrator when the novel begins; he grew up in Berlin and was, like his narrator, a citizen of Czechoslovakia (citizenship he inherited from his father), where the family ended up moving in 1936. But whereas the narrator separates from his parents early on and goes to Spain to fight against the fascists (the bulk of Volume I), Weiss and his family emigrated to Sweden after the annexation of the Sudetenland, where he would remain for the rest of his life. In Volume II, the characters land in Paris, dejected and defeated after Spain, at which point they flee to Sweden, where they meet up with Brecht (around whom there is “brightness, unbounded imagination”) and have lengthy debates about how to respond to the Soviet Union’s new alliance with the Third Reich, while the narrator works together with Brecht on an unrealized project to dramatize the life of Engelbrekt Engelbrektsson (a Swedish nobleman who led a rebellion against the Kalmar Union). It is at this time that the narrator reconciles his political and literary ambitions and resolves to devote himself wholly to a kind of kunstpolitik (“political judgment, relentlessness in the face of the enemy, the power of the imagination, all of this came together to form a unity.”)

Weiss’ characters don’t have the means to arrange a gap year or wanderjahr for themselves. Instead, they have to steal their education out from under the drudgery of factory life and state oppression, meeting in secret, in kitchens, basements, and factory floors to discuss classical art, Dante, or Rimbaud. Their auto-didacticism is promethean: “[O]ur most important goal was to conquer an education,” the narrator says early on in Volume I, “a skill in every field of research, by using any means, cunning and strength of mind. From the very outset, our studying was rebellion. We gathered material to defend ourselves and prepare a conquest.” Ultimately the question that preoccupies The Aesthetics of Resistance is the same question that preoccupies any bildungsroman: how does education — in this case, aesthetic education — provide the moral coordinates that prepare one for the (often harsh) realities of political life? Could a bildungsroman that takes place under the buckle and boot of fascism look otherwise?

Politics has always been part of the landscape of the bildungsroman (the reactionary conservatism of the Bourbon Restoration in The Red and the Black; the revolutionary upheavals of 1848 in Sentimental Education; the backdrop of the Irish Independence movement in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man) as has the attempt to eschew politics from it. I’m reminded of a passage in The Red and the Black where a reactionary author remarks that “politics is a stone tied to the neck of literature,” which, “in less than six months, drowns it.” Not content to stop there, he presses on: “Politics in the middle of imaginative interests is like a gun shot in the middle of a concert… It is not in harmony with the sound of any of the instruments.” Weiss’s bildungsroman, which bucks this prejudice to the nth degree, has to deal, whether it likes it or not, with just such gunshots, and in so doing reveals the ways in which politics are inseparably infused with imaginative interests, even when they collide. At one point, while in Spain, Weiss’s narrator alludes to the “clash between politics and literature” a phrase that echoes Lionel Trilling’s description of the “dark and bloody crossroads where literature and politics meet.” The Aesthetics of Resistance, which sits squarely in the middle of this crossroads, is a brutal dramatization of this collision, and is as clear an example as any I can think of (to borrow Orwell’s phrase) to “make political writing into an art.”

Volume I begins with a description of the Pergamon Altar. The narrator and his comrades, Hans Coppi and Horst Heilmann (real figures of the anti-fascist resistance) are walking through the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, as scarlet flags fly in the square and air raid sirens blare from the loudspeakers. We’re given a vivid ekphrasis of the altar’s east frieze, which depicts the Gigantomachy, the mythical war in which the Giants rebelled against the Olympians, in the contorted forms and agonistic expressions typical of Hellenistic art. The characters interpret the frieze as an image of class struggle, in which the Giants attempt to vanquish their Olympian oppressors. Their reading also contains a strange inversion: Heracles, the only mortal called upon to help the gods, is identified as a liberator (having freed the Peloponnese of monsters) and an “advocate of action.” His lacuna in the frieze opens the space to make this interpretation possible (his absence “marks the hope for liberation,” presenting “the subject of history as an empty space still to be filled.”) In their reading of an eternal class struggle into the altar (which reminds me of an anecdote that some Bolsheviks carried around copies of Paradise Lost to inspire them in their fight against Tsarism) the characters are trying to locate within the past some parallel that illuminates and strengthens them against the perils of the present. In the Gigantomachy, Weiss is aware that this is a work that occupies a different historical moment, but one that can be reconstituted (not appropriated, but understood anew) in the context of one’s own historical moment, and that this demands interpretation––that is, “to treat [works of art] against the grain” and “project our own demands into them.”

The altar was dedicated in the 2nd century BCE to commemorate the Pergamene victory over the Celtic Galatians and was likely built by the very people who had been made slaves in their defeat. It was excavated in the 1880s by Carl Humann, a private citizen, and shipped stone by stone back to Berlin, as part of the newly unified German Empire’s effort to compete with the cultural capital of its rivals, a competition that would eventually drag the entire continent into the abyss. The Nazis, who appropriated classical aesthetics to their own ends, saw in the altar an apocalyptic struggle for dominance and the triumph of the strongest. Under the direction of Albert Speer, architect Wilhelm Kreis was commissioned to design a military monument at the foot of Mount Olympus in Greece meant to resemble the Pergamon Altar, a project that (mercifully) never materialized. After the war, pieces of the frieze were seized by the Red Army and taken back to Leningrad, where they were displayed as a symbol of the Soviet Union’s victory over fascism. Thus, to read the Pergamon Altar against its own grain is to understand the ways in which cultures have projected their own demands onto it throughout history. For the narrator and his comrades, their interpretation is in direct defiance of “The monuments of fascism, based on Greek, on Roman models,” which “communicate nothing but plaster emptiness.” Before the narrator and his comrades, “this mass of stone now [became] a value in its own right, belonging to anyone who steps in front of it.” It is also fitting that the novel opens in the Pergamon Museum, as museums rip works from the contexts in which they were made to be experienced, and are themselves tense symbols of civilization, displaying cultural riches while also being monuments to the reaches of imperialism (critic Adam Kirsch is right when he points out that Weiss would have likely agreed with Walter Benjamin’s statement that “there is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.”)

Still, one might ask, what are these characters doing standing around in museums, discussing Hellenistic art as Nazism gears up to unleash horror upon Europe, and how could this be considered a form of resistance? It might seem like a kind of withdrawal, a retreat from one’s responsibilities and the realities of life, until we remember that one of the Nazis’ first symbolic displays of their power was a night of book burning. Freud, Brecht, Marx, Kafka, Döblin, Broch, Kraus, Hesse, Heine, were just a few of the authors tossed in the fire, while the category of “kulturbolschewismus” and “degenerate” art was wide enough to swallow up Cubism, Expressionist cinema, General Relativity, and quantum mechanics. Under such a hideous, indiscriminate assault, museum-going and poetry readings suddenly seem like acts of resistance indeed (anyone who has lived under a totalitarian regime can attest that discussing literature in a kitchen is very much an act of resistance). One of the things that distinguishes totalitarianism from other kinds of state tyranny is the way in which it invades every nook and cranny of human existence and seeks to colonize the mind. That is, it makes apolitical life impossible, thereby rendering impossible any apolitical treatment of art. The old cliché that no one takes art more seriously than the censor is obviously untrue, but it is true that the political hand of art, and thus its threat, is often forced by its oppressor. Confirming this, the narrator says shortly after they return from the museum:

Our road out of intellectual suppression was a political one. Anything referring to poems, novels, paintings, sculptures, musical pieces, films, or plays had to be thought out politically. This was a groping, we did not yet know what use our discoveries would be, all we understood was that in order to make sense it had to come out of us.

This is because:

We felt ourselves to be at the mercy of a politics that could not be influenced and that crushed all individual considerations. The nightmarishness of it resided in the fact that a seemingly unreal entity was claiming to be the sole representative of reality.

It is not crude politicization, therefore, that the characters are engaged in, but a matter of necessity, for the preservation of dignity, the overcoming of ignorance and degradation, and ultimately for survival. It is an attempt to recover a sense of reality other than the one that has been imposed upon them. But it would be wrong to view this as simply instrumental, as if art were merely one of the available tools against fascism. It is an effort rather to cultivate that which no state can presume to create nor hope to destroy. As Hodann, one of the characters, puts it: “[A]rt had to compensate for part of what politics left unfulfilled. Art inhabits the same space as politics, but politics has diverged so far from everything we desire that its guidelines now seem like nothing but misguided restrictions.”

This sounds remarkably similar to the argument made by Schiller in On the Aesthetic Education of Man, published in 1794, largely in response to the perceived failures of the French Revolution and its descent into bloodshed and terror. One of the reasons why the revolution failed, Schiller posits, was that it ruled by injunction and failed to cultivate a “capacity for feeling” after abolishing the society’s spiritual institutions. States (not just revolutionary or tyrannical ones) are disposed to rule in just this way: as bureaucratic, rational entities, they are institutionally unsuited to cultivate the “moral possibility” that is at the same time necessary to keep the State from devolving into barbarism. “We should need, for this end,” Schiller writes, “to seek out some instrument which the State does not afford us, and with it open up well-springs which will keep pure and clear throughout every political corruption… This instrument is the Fine Arts…” Aesthetic education, which is generative, communitarian, solidarity-giving, is thus a necessary counterforce to the conditions, obligations, restrictions and brutality of political life. Sounding an awful lot like one of Weiss’s characters, Schiller proclaims that: “The political legislator can enclose their territory, but he cannot govern within it. He can proscribe the friend of truth, but Truth endures; he can humiliate the artist, but Art he cannot debase.”

The question of how experience and aesthetic education lay the moral foundation that prepares one for political life infused the revolutionary epoch at the end of the 18th century and found dramatic expression in — surprise — the bildungsroman. It also found expression, a little belatedly, in Romanticism, a movement that, at least in the English tradition, was closely allied with radicalism and republicanism. Romanticism can be seen as an attempt at transvaluation, the kind that revolutionary moments call for, by fashioning an ethics out of aesthetics, in order to recover a sense of “moral possibility.” Indeed, Percy Shelley’s whole notion of the poet as an “unacknowledged legislator” directs us to the ways in which literature and art are the source of the moral law without which we cannot hope to have a civilization.

If this question seems contrived or remote to us, it is because we no longer occupy a moment in history in which such questions are pressing upon us. For the Modernists, certainly, the relationship between radical politics and radical aesthetics was obvious. More still, many revolutionaries recognized it to be urgent. In 1923, barely a year after the Russian Civil War and with the new Soviet economy in shambles, Trotsky wrote Literature & Revolution in an attempt to address this very matter. Economic problems, Trotsky makes clear in his introduction, are “the problem above all problems” but stresses that a new society cannot understand itself, let alone survive, without art: “In this sense, the development of art is the highest test of the vitality and significance of each epoch.”

The question of revolutionary values also occupies Weiss’ 1964 play Marat/Sade (the full title of which is The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade) which takes place in 1808, when France is under Bonapartism. In part, it is a dialogue between Jean-Paul Marat and the Marquis de Sade, a dialogue, conducted absurdly yet entirely appropriately in an insane asylum. (There is a kernel of truth here, as de Sade apparently did stage plays in Charenton using inmates as his actors.) It is a dialogue conducted, contra Hegel’s definition of tragedy, between the Wrong and the Wrong: the debate is whether the revolution will open the door to a kind of runaway individualism (represented by the solipsism and moral perversion of de Sade), or the crushing of the individual conscience under the collective will (represented by Marat). It is a version of the same debate that informs any revolutionary moment: whether societies change first by changing their people, or their institutions. But in Marat/Sade, just as in The Aesthetics of Resistance, the revolutionary moment has passed, and the characters now find themselves on the defensive, in an epoch where questions of aesthetics are as much about the transformation of values as they are about hanging on to life.

Volume I closes with a meditation on Picasso’s Guernica, as the narrator and his comrades find themselves run out of Spain after a crushing defeat. Picasso’s painting is a calamitous landscape — much like the Pergamon Altar and Weiss’s own novel. It is also a painting that owes its existence to the efforts of the anti-fascist forces in Spain and France: it was commissioned by the besieged government in Madrid to help bring global attention to the war, and it was Picasso’s lover at the time, the photographer Dora Maar — a figure in surrealist circles in Paris — who procured the space for him to paint it, in a studio on the Rue des Grands-Augustins, which had been used as the headquarters for Contre-Attaque group founded by Georges Bataille, where artists and intellectuals regularly met to read their work and make anti-fascist speeches. Following a long, ekphrastic passage, the narrator, ventriloquizing Picasso’s own assessment of his work, writes:

His entire life, [Picasso] had explained at the conception of this painting, was nothing but a never-ending struggle against the backwardness of thinking and against the death of art, and these words meant reactionism’s encroachment on the people and on freedom in Spain. He equated the struggle for truth in art with the rebellion against demagoguery, for him artistic labor was inseparable from the social and political reality. The destructiveness descending on Spain was meant to wipe out not only people and cities, but also the ability to express things.

The last sentence here is key: Guernica depicts not just the monstrous violence and cruelty of fascism, but an assault on the sensibilities, the very thing that renders such expression possible in the first place. Like Shelley’s unacknowledged legislator, Picasso’s painting may have come too late; it didn’t prevent destruction, or change the course of the war, but it has opened up a moral space for understanding that war and the many crimes committed during it. There is also no more enduring and resonant image of the Spanish Civil War, and it is one that has outlasted all the machinery of death, every bomber, every fighter pilot, every general and bureaucrat, every lie and deceit, and every equivocation and justification made in its name.

For the people who lived through it, they believed the Spanish Civil War to be the decisive event of their epoch, unaware that it was only a dress rehearsal for the disaster to come. It also pointed the way to future betrayals: the Soviet Union’s abandonment of the Republican forces was just another in a long line (the suppression of the Kronstadt rebellion, the expulsion of Trotsky, the purges and the Moscow Trials) but it did presage the ultimate betrayal that came with the collaboration with Hitler in 1939, and this is the second front (if you like) of the resistance referred to in the novel’s title — the simultaneous struggle of the left opposition to Stalinism. By the time Weiss was getting ready to begin work on the book, in the late 1960s, he found himself similarly pinched, opposing the American involvement in Vietnam as well as the fresh betrayal of the Warsaw-Pact Invasion of Czechoslovakia, the country of which he’d originally been a citizen.

Some readers might question the value of rehashing so much leftist insider baseball. But to remain ignorant of the left’s struggle against fascism — and its struggle within itself — severely distorts one’s understanding of the 20th century. Still, the question of relevance presses upon the text. Noah Isenberg, reviewing Volume I for The Nation in 2005, wrote: “In spite of the admirable effort to publish the first volume… one doubts whether the novel will ever find much of an audience in the twenty-first century.” (One doubts he would feel the same now, from the vantage of 2025.) Conversely, Ryan Ruby’s essay “Resisting Oblivion” (published in The Point in 2021) explores how The Aesthetics of Resistance could be read in light of the first Trump presidency.

But a novel’s relevance isn’t limited to simple parallelism, i.e. how easily we can uncover analogies between it and our own time. This is a question, however, that is internal to The Aesthetics of Resistance itself. Early on in Volume I, shortly after the characters return from the Pergamon Museum, the narrator voices his attempts to understand what relevance their discussions about art have to their current predicament: “[F]irst you had to overcome the generations-old compulsive idea that the book did not exist for you. On Sundays we sat in the Humboldt Grove or in St. Hedwig’s Cemetery, near Pflugstrasse, trying to find out what the Divina Commedia had to do with our lives.” Indeed, one might ask (a little disingenuously) what relevance a 14th century epic poem has to life in the Third Reich in 1938. But then one could easily ask what relevance Homer had to Dublin in 1904, or the Grail Legend to Europe post-WWI. Such questions make plain that pinning any work of art to the present on the basis of “relevance” is myopic, even shallow. What is at stake rather is the notion that our relationship to the past is essentially imaginative and that our understanding of it is always being reconstituted to meet the moral and aesthetic demands of the present, an ethos that suffused Modernism and which Weiss absorbed thoroughly.

We get something like an explication of this very idea near the end of Volume I, in the thick of the narrator’s meditation of both Guernica and Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa:

Nevertheless, in transposing an actual event to the range of art, the painters had succeeded in setting up a monument to radical instants. They had shifted experience to their own present, and we, who saw each crystallization, brought it back to life. What was shown was always different than what it had emerged from, a parable was shown, a contemplation on something in the past. Things drifting by had become something lasting, freestanding, and if it possessed any realism, that was because we were suddenly touched by it, moved.

If history or the literature of the past seem remote from us, part of what it means to undertake an aesthetic education is to arrive at some understanding of how they are relevant, and this, I submit, is the very effort that The Aesthetics of Resistance represents, both internally (for the narrator and his comrades), but also Weiss himself in writing the book, as the composition of the novel itself constitutes something of the author’s attempt to re-educate himself, to erect a similar monument, to remind himself of what he knows, what his generation has passed through, and why it shouldn’t be forgotten.

History has a biological threshold; it exists for only so long until it exits living memory and becomes an abstraction. The horrors and crimes of the twentieth century are presently at that threshold and are now in danger of turning into the stuff of textbooks, as they recede further into the past. Weiss’s novel, which he described once as a struggle against “the art of forgetting” hardly needs to cry out for relevance at a time when an awful lot of forgetting seems to be going on and we seem quite ready to repeat our mistakes.

Art is one form of remembrance, and it is through the work of historical memory that the past is activated. “Our relationship to art,” Weiss remarked in a 1981 interview with Burkhardt Lindner, “is nothing other than some inventory we have within ourselves, some reservoir of things that constantly enables us to actualize our experiences, isn’t it? It comprises all periods of time… it is indeed the only permanent thing in the midst of all the upheavals and struggles that have taken place time and time again.” This is echoed in The Aesthetics of Resistance when Heilmann says, “All art… all literature are present inside ourselves, under the aegis of the only deity we can believe in, Mnemosyne.”

The imagination outlasts all events, contingencies, regimes. Again, Guernica has outlived everything and everyone from the Spanish Civil War. But that is true only as long as we continue to engage with it. Like the characters reading their resistance into two-thousand-year-old stone from Pergamon, works of art must be continuously reimagined, reinterpreted and seen anew. By way of a strange congruence, Guernica appears briefly in Children of Men (2006), a film about the literal collapse of the future, as the fertility rate on the planet has dropped to zero — there are no more children being born, and Western democratic countries have all devolved into something like fascist police states. In one scene, Picasso’s painting is seen hanging in the dining room of a private collector. The painting, while still a work of genius, while still a memorial, is effectively inert, for it exists in isolation — no one is able to view it, and soon enough, none will be able to view it. So too for Weiss’s narrator and his comrades, even though they seem to be living in an apocalyptic time, their engagement with these “radical instants” from the past presumes futurity. That is, it presumes there will be a future in which the past still matters.

Engagement with art and literature is a way of turning towards the world, towards reality, even in a state of captivity or desolation. “But this path” as the narrator says — that is, the path to art — “only remains open so long as there is a willingness to address the outside world… The border between closing oneself off and opening oneself up, which bears the promise of a cure, is always present in art…” We know that aesthetic experience and expression can survive in even the most hostile and dehumanizing conditions. There was literature in the gulag, there was painting in Auschwitz, there was poetry in the trenches. “Imagination lived so long as human beings who resisted lived,” as the narrator says. “However, the adversary aimed not only at material devastation but also at the snuffing-out of all ethical foundations.” And therein lies the essence of the aesthetics of resistance — rather than simple resistance: there is the tacit recognition that any triumph over fascism is ultimately incomplete if it doesn’t recover the fundamental moral supports of human existence, without which not even the past is safe. Weiss’ novel shows that not only can one not live in such times without art, but that aesthetic education is necessary for survival, especially when the brutality and misery of political life threatens its existence, when the space for aesthetic contemplation shrinks, or seems secondary to more immediate concerns. Even though it is a chronicle of defeat, demoralization, murder and calamity, The Aesthetics of Resistance, as an act of remembrance, as an engagement with the past, with art and literature and the things that exist under the umbrella of eternity, nevertheless opens up an inspired space for thinking about the future of humanity. Memory, after all, is the Mother of the Muses.