I was in Shangri-La, in a village in the Tibetan Himalayas on October 7th, 2023. More precisely, I was in the Shangri-La tourism zone of Yunnan, a popular Chinese travel destination marketed as the “true location” of a legendary hidden utopia in the Tibetan mountains. My Israeli husband, Gil, sent me a message on my Chinese social networking app, saying: “War has started. Check the news!”

At first, I thought Gil’s words were metaphorical. There could have been a new development in the ongoing Israeli protests against Netanyahu’s extremist government, and I wondered if Gil might be referring to a war of ideals between the pro-democracy activists and the ultra-right settler government that was steering towards a Jewish theocracy. I imagined Gil was referring to a war for human rights, for equality, for compassion, for an end to the occupation — a war for peace.

It took me a few hours to understand it was no metaphor.

Gil asked me to call him on my back-up phone on which I had installed VPN software to circumvent the firewall that isolates the government-censored Chinese Internet from outside media. This is how I learned that Hamas had broken into the Israeli farming communities near Gaza to kill and abduct people who were just waking up on a Shabbat morning. Nobody knew yet what exactly was going on. Gil was texting with family and friends back home in Israel as they reported on the whereabouts of their children, family members, friends, friends’ children, and children’s friends — which, in the following days and weeks, would turn into updates on funerals and abducted-person reports.

I had been avoiding the internet because I was traveling in China as a journalist and worried about surveillance. I was staying at the farm of a villager whom I had hired as a driver. Aware that the Chinese authorities track all cyber activity, I feared I’d somehow implicate myself or my host.

But now I realized that people I loved could be dead and I wouldn’t even know. I furtively used my VPN to read the news, sitting in the shade in a corner of the yard, with the tok-tok of walnuts falling onto the metal roof of a shed. When I saw the images of blood-splattered walls and dead bodies, I quickly exited the browser, afraid to find out more. The desperation online contrasted so violently with the calmness of the village that it almost gave me vertigo. What does one do with so much pain so far away? And this was before the Israeli army had entered Gaza, razing whole cities and killing tens of thousands of people, until the horror of what happened on October 7th was drowned out by the slaughter in Gaza.

“I can’t go on like this,” Gil cried when we spoke again two days later. He was on an academic exchange program in Taiwan for the American university where he teaches. Alone in his hotel room, he hadn’t been able to sleep for two nights in a row, obsessively glued to his screen to follow the news and keep up with messaging threads. He told me that our friends Arik and Marganit were busy helping their neighbors locate their 22-year-old daughter, Lin, who had gone dancing and never came home. It eventually turned out she had been killed, her body so mutilated it took the police weeks to identify her remains. I wanted to end my trip and join Gil in Taiwan, but he insisted it didn’t make sense. There wasn’t anything either of us could do from the other side of the world.

Our own kids were back in the US, in college. When I called them — our son in New York, our daughter in Massachusetts — and asked how their classmates responded to the news, they said they avoided talking about the war. They kept busy with school and work, hiding from the furious rhetoric that was already overtaking American college campuses.

Gil and I met as students in Israel, not long after my family had moved there from Amsterdam. Life and work eventually brought us to the US. We had vaguely intended to return eventually to Israel. But the years turned into decades, and every trip home confronted us with how Israeli reality had grown further away from the Israel of the 1990s frozen in our minds when we left; the Israel we thought we would return to, a country in the midst of negotiating a two-state compromise with the Palestinians, a country that we had believed to be on the brink of peace.

And now we live in America and have American children who avoid getting involved in activism and are unsure about their relationship to Israel, even though they have grandparents and cousins there, have spent almost every vacation on family visits in Israel, speak Hebrew, and went to Israeli schools during a sabbatical we spent there. Perhaps they just pretend not to care because that’s how they deal with the confusion of having an impossible mix of identities in a divided world.

I spent a whole afternoon on a plastic-wrapped couch in the farm kitchen beside the Wi-Fi router, trying to find out what had happened to friends and family, making sense of the news, and furtively calling Gil and my kids. I was paralyzed with worry about the unfolding war, and afraid that all my VPN activity on the village network would get me or the farmer in trouble.

I had been trying to keep a low profile because I was attempting to stealthily research two articles I planned to write: one on how Xi Jinping is co-opting Buddhism to strengthen the Chinese Communist Party’s hold over Tibet, and another about an early-20th-century adventurer who sought, in Tibet, an escape from the everyday world. But then I found myself in tears, hogging the village internet. When I finally explained to the farmer why I was upset, he nodded. He had heard some version of the events on the Chinese news. “There’s nothing we can do when our governments fight wars,” he tried to console me. “We regular people are powerless. Just ignore the politics and take care of yourself and your family! We must carry on!”

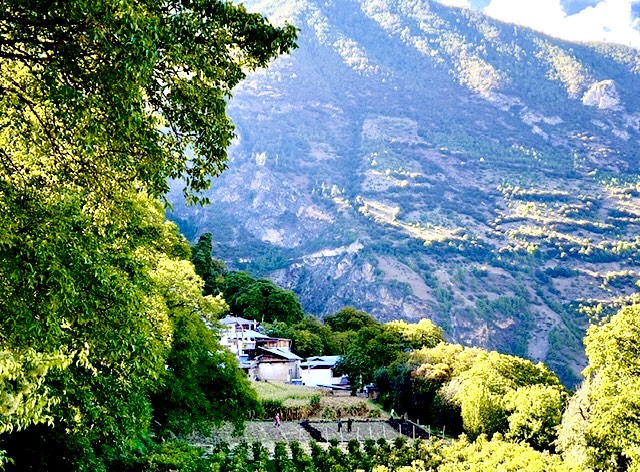

His village was in a contested Tibetan region near the Myanmar border which, for centuries, had been fought over by different governments: from local kings, to the Dalai Lama’s government in Lhasa, to the Chinese Qing Empire, to warlords during the Chinese Civil War, to the Communists, to Mao Zedong’s Red Guards, and now, of course, Xi Jinping. Each ruler tried to erase what had been established by previous governments and reshape the local culture and ideology according to their own worldview. Currently, the village wasn’t doing too badly. The Chinese government had invested billions of dollars in tourism development and had officially renamed the region “Shangri-La,” after a popular British novel about a magical hidden mountain paradise. The tourism industry was thriving, and the village successfully exported a local wine that was in demand all over China. Many villagers, like my host, earned extra bucks as tour guides and drivers. The slopes of the mountain were parceled up in luscious vineyards, amidst each of which stood a large farmhouse with a shiny new car. Right next to the Buddhist stupa that adorned the highest tip of the ridge near the village, a large cell-tower provided fast phone and Internet connections.

The farmer’s ancestors had obviously been amongst the survivors of the many local wars and persecutions. They had been the ones who adapted in whatever ways were necessary to carry on, as he did now, with a communist flag on the dashboard of his new car and a picture of President Xi Jinping by his Buddhist altar.

I couldn’t explain to him that Israelis and Palestinians don’t have the option to just “ignore politics”; that they are their nations’ politics and ideology, or, at least, are presumed to be.

In the group chat of our Israeli college friends — many of whom are now teachers, academics, non-profit organizers, and writers — the conversation in the previous months had been alternating between birthday congratulations and political analysis, to the logistics of organizing protests against the occupation and against the aggressive politics of Netanyahu’s radical right-wing government, which aimed to annex the occupied Palestinian territories and establish Jewish supremacy. For a while, our friends traveled almost every Saturday to a Palestinian neighborhood in East Jerusalem to protest in solidarity with the local Palestinians whose houses were taken over by settlers and threatened with demolition. Gil and I joined them when we visited.

Our friends have inherited their vision of Israel from their parents and grandparents, who arrived as refugees hoping to find a place where Jews could live in a just society, free from persecution. In his 1902 novel Altneuland, the Zionist thinker Theodor Herzl describes an imagined country where Jews, Muslims, Christians, Buddhists, and people of all religions live together in equality and harmony. A Palestinian character in the book warmly describes how his Jewish neighbors “dwell among us like brothers.”

How could it have gone so wrong?

A few years ago, a Palestinian friend in Gaza asked me to send him a picture of his family’s ancestral neighborhood in Jaffa, less than 40 miles from the refugee camp where he grew up and still lived. Since his childhood, Gaza has been sealed off from the world, and the 40 miles between his house and the house his grandparents had fled 70 years earlier were unbridgeable. I felt guilty that I could walk around freely in a place he could only dream of. I could even stop at an ice-cream store that possibly belonged to a remote relative of his who descended from a branch of the family that had stayed put in 1948. Without an address or a street name to go by, I sent my friend a photo of the prettiest house I saw in the neighborhood: an old stone villa, plastered pink and decorated with an abundance of potted flowers. My friend thanked me so profusely for the picture that I worried he really thought this was his ancestral home and now imagined old Jaffa as a rose-colored city filled with flowers.

And who doesn’t want to imagine a rose-colored past? Or a bright future? Or some alternative realm, away from pain and conflict?

The Tibetan village where I was staying could have been transposed from an imagined Mediterranean paradise. It was built on the slopes of a mountain valley which, through a miraculous confluence of meteorological factors, sheltered a temperate micro-climate of eternal summer. While a winter chill had already set in down below and snow was falling up on the Tibetan plateau, the village bloomed with an abundance of bougainvillea, grapes, pomegranates, and pomelos. Along the trails at the edge of the village even grew prickly-pear cacti laden with sabras. A copper prayer wheel – a cylinder filled with a prayer scroll – spun in a nearby brook. Propelled by the force of the water, it sent, with each turn, a plea for redemption into the universe. As I nibbled pomegranate seeds from a freshly picked fruit, I gushed to the farmer that his village truly seemed to be Shangri-La. He smiled in agreement.

Gil and I used to live in a Southern neighborhood of Tel Aviv, almost bordering Jaffa. We were still so hopeful then. It did not seem impossible to find a way to live in peace on that land.

On Saturdays, when the public buses didn’t run, I often walked from our rental apartment to the beach. I’d pass through the narrow streets of dilapidated two-story houses, which in the 1930s had been the apex of Tel Aviv modernism, but which were now covered in soot and turned into discount stores and slum rental apartments. At the edge of our neighborhood lay a stretch of wasteland taken up by car repair shops and impromptu parking lots. There, I’d pass the skeletons of old stone villas that offered a refuge to addicts and feral cats but that had once been part of a Palestinian neighborhood built in the late 19th century, when the area became a coveted place to live for wealthy Arabs and Jews who wanted to escape the crowdedness of old Jaffa and be near the new train station that offered a daily connection to Jerusalem and later to Gaza. As I walked amongst these traces of the past, I imagined a world in which Jews, Muslims, and Christians shared the land and Jaffa was just a short train ride away from Gaza.

Eventually, I learned that already back then the region seethed with conflict. There was discord and violence, not only between Arabs and Jews, but also amongst Jews and amongst Arabs. Muslims had misgivings about Christians, Sephardic Jews kept their distance from Ashkenazi Jews, the fellahin were wary of city folk, religious conservatives objected to secularists, the Husayni clan quarreled with the Nashashibi clan, the Marxist Communists opposed the Socialist Zionists, the Socialist Zionists denounced the revisionists, the Misnagdim resisted the Hassidim, and both Misnagdim and Hassidim rejected the Zionists. Everyone competed and fought for their own vision, in conflicts that still shape today’s wars and politics.

Shortly before October 7th, our friends in Israel still sounded upbeat. Despite their dread at the extremism of the new Israeli settler government, whose embrace of violence and war matched Hamas’s fanaticism, the group chat was optimistic. All over the country, Israelis were gathering in mass protests against the government, and it looked as if Netanyahu might be toppled. Every day, our friends shared photos of themselves at some demonstration, followed by logistical chats to decide where to meet for the next protest. Because you can’t just give up. Unlike the Tibetan farmer, we couldn’t just ignore politics. We still thought that if we persisted, a better reality might be over the horizon, almost in reach.

And then, in the early hours of a Saturday morning, Hamas militants attacked, killing more than 1200 people and kidnapping close to 250 into Gaza. The victims, most of them from the kibbutzim near Gaza and young people who had attended an outdoor rave near kibbutz Re’im, tended to be left-wing idealists who opposed Netanyahu and believed peace was possible, like ourselves and our friend group. In fact, some of them were friends and family of our friends.

Many of the victims had been activists for peace and coexistence. There was Lilach Kipnis, a child trauma specialist active in the Israeli anti-war movement, who was murdered in her house in Kibbutz Be’eri. There was 19-year-old Naama Levy, abducted to Gaza, who participated in the organization “Hands of Peace.” There was Hayim Katsman, a researcher who volunteered for Academia for Equality, an organization supporting Palestinian academics, who was killed hiding in a closet at his home in Kibbutz Holit. There was Hersch Goldberg-Polin, a young man abducted into Gaza and later killed, who was a dedicated supporter of the anti-racist soccer team Hapoel Jerusalem, and a good friend of the son of our friends Jessie and Yuval. And there was Vivian Silver, a prominent peace activist who, amongst other things, was a cofounder of Women Wage Peace. Three days before she was killed in Kibbutz Be’eri, she had helped organize a peace rally in Jerusalem.

Their idealism didn’t protect them. And all over the world people cheered their deaths and abduction as an act of resistance against the “Zionist occupation.” A Palestinian teenager I know wrote on Facebook: “We are so proud of what Hamas has done.”

No one seemed to notice or care that the victims were not the Israelis who terrorized Westbank villagers and called for the subjugation of Palestinians but the ones trying to make peace.

And of course it shouldn’t matter. Because that’s not why one commits to peace: not as an assurance to be spared when war erupts. You don’t get to be exempt because you’ve tried to be “good.” There is no neutrality in war, or life. It’s a luxury to think you can avoid the violence of the world.

Later came the reports from Gaza: the images of dead children, of people digging out their relatives from underneath blocks of concrete, of hungry families, of starving bodies, and of hospitals running so low in essential supplies that limbs had to be amputated without anesthesia. My friend in Gaza posted a video of his house, destroyed in an airstrike in the third week of the war. And then he posted a photo of one of his students who was killed along with his family, and then of a colleague who died along with her parents, and then of a close friend who was killed, and then of his wife’s uncle, and then of his soccer coach. I messaged him my condolences after his first losses, but as he kept posting images of dead friends and family members, I was paralyzed with sadness and despair. He never responded to me. Understandably. What can a Palestinian say to an Israeli while the Israeli army is killing his family and friends? His posts drew plenty of responses from other people: “Judgement is coming for Zionazi criminals and their accomplices,” a person named Lauri commented on one of his Facebook posts.

Is this what the ideal of “a safe homeland for the Jews” has brought about? Not a refuge; but an endless war that divides everyone against each other?

I used to believe in the power of compromise, kindness, and goodwill. But it’s difficult to preserve that faith. When is it time to give up hope? Gil and I already gave up years ago, even though we refuse to acknowledge it. Now, many of our friends are talking about leaving Israel. Whole communities of Israelis are resettling in places like Berlin, Amsterdam, Portugal, and even Thailand. That has been the traditional Jewish response: to withdraw to safer grounds when things get bad, from diaspora to diaspora.

But even losing hope is a privilege. Not everyone has the option to give up and leave. And what if, in reality, there is no hope? What if there never was? What if hope is just a mechanism for survival?

The article I was researching in China was about Xi Jinping’s co-opting of religion to bolster his power. Communism was supposed to have ended oppression and inequality. It had promised to establish an international workers paradise on earth. But instead, the Communist government had mobilized a whole army to silence dissent and ensure complete obedience to the Great Chinese Motherland. Now, China was experiencing a resurgence of religion because nobody believed in Communism anymore, and Xi Jinping, a clever Marxist politician who sees religion as a drug, or tool, to distract people from demanding change, was promoting “patriotic Buddhism,” which looks similar to traditional Buddhism but which above all exalts Xi Jinping and the party.

That was how the village had prospered. Elsewhere in Tibet, Buddhist monks were detained for resisting the government’s policy of subsuming Tibet into China. But the villagers had embraced Xi Jinping’s patriotic Buddhism and were in good favor with the authorities. The central government had invested heavily in infrastructure and development and held up the local Buddhist monasteries as models of patriotic Buddhism. The farmer’s son and daughter were both attending government boarding schools intended to transform young Tibetans into loyal citizens of the great Chinese homeland.

On my last afternoon in the village, I went on a hike in the mountains with the farmer’s 18-year-old son who was home from boarding school. I had asked him to show me the pilgrimage route on which a French explorer had set out into Tibet a hundred years earlier, which had been my reason for coming to this particular village. In my childhood, I had come under the spell of the explorer’s account of Buddhist magic and the enchanted Tibetan wilderness. I had dreamed of standing at the foot of these mountains and wanted to believe I would somehow find a crack here that offered entry into another world.

The farmer’s son knew the way so effortlessly that he could watch tik-tok videos on his smartphone while skipping from rock to rock.. Every once in a while, he chuckled and stopped to show me some American college kids pranking each other or two guys farting in sync.

“My parents don’t know very much; they’re just farmers,” he had confided to me earlier, as if we shared some superior understanding. When I asked him about his plans for the future, he told me that, although his father wanted him to go to university, he first planned to enlist as a soldier in the Chinese army, “to build character and become a real man.” He insisted he wasn’t afraid of war or the prospect of an invasion of Taiwan. “Taiwan will be liberated,” he declared patriotically. “Either they will join the motherland willingly or we will take them by force!”

This Tibetan kid, so willing to sacrifice himself to conquer others, didn’t seem to be aware that in a previous generation many of his Tibetan compatriots had died fighting against the Chinese Communist “liberation” of Tibet.

I didn’t respond, but my sympathies were with the Taiwanese and with the Tibetans who fought to try and preserve their traditional way of life — a way of life that, the Communists argued, was steeped in feudal oppression. This may have been true. But it’s not as if the Communist “liberators” brought equality and freedom. That’s how humans are: with every problem we try to solve we create a bigger one.

Ten days later, I continued to the Tibetan highlands where I found myself in a dark chapel in a town called Litang. I had traveled there to visit a monastery that seemed particularly well-off and well-favored by the authorities. The monastery enjoyed a steady stream of tourists who came up from the big coastal cities of China. During the Tibetan uprising of the 1950s, the Red Army had bombed the monastery, killing hundreds of monks and resistance fighters who thought a place of worship would provide them safety. The monastery was now gorgeously rebuilt. The main shrine, spacious like a gothic cathedral, housed an enormous gold-plated Buddha statue, and its walls and pillars were decorated top to bottom with exquisite murals. A bright red communist flag flew on top of each golden rooftop.

But at the foot of the large monastery, just outside the enclosure wall, was a small chapel that seemed to have been overlooked. I had followed a grandmother and her granddaughter on their morning walk around the monastery, a simple act of worship for those who can’t express their devotion with lavish donations. In an alley below the monastery, they entered a courtyard lined with battered prayer wheels, which led to a small temple. In the dim shadow of the windowless chapel, devotees quietly murmured mantras and circled clockwise as they spun large prayer wheels that filled the space like a maze of magical merry-go-rounds. The constant touch and motion had worn off the painted flowers and goddesses that decorated the copper cylinders. The prayer wheels resembled giant mezuzahs, the cases that are traditionally affixed to the doorways of Jewish homes, and which observant Jews touch with every entry and exit to acknowledge the power of the sacred text enclosed within. An old woman, her back twisted by age and rheumatism, smiled and offered me a knotted rope that served as a handle to set the prayer wheel in motion.

She reminded me of our elderly neighbor in south Tel Aviv who had arrived as a refugee from Iraq in the 1950s. Day in and day out, she would sit on the bench on the sidewalk outside her one-room apartment, shelling peas, mending clothes, or reading her siddur (prayer book). In the darkness of the house, her ailing husband lay propped up in a hospital bed, peering out of the door which always stood open so he would have a view. When I stopped by to say hello, she used to clasp my hand in hers and bless me.

The old Tibetan woman motioned for me to spin the prayer wheel, and as I joined the choreography of devotion, I felt overwhelmed with sadness. It was as if the temple had absorbed the despair and resignation of all the worshippers who had ever spun those prayer wheels seeking relief amidst wars, violence, poverty, oppression, pain, fear, and dashed dreams.

The first of the Buddha’s teachings is that suffering, dukkha, is at the essence of existence. The world is terrible — and will always be terrible. There is no escape. There is no utopia in the mountains of Tibet, nor anywhere else in the world.

But still I can’t let go of hope. Because…what else do we have? We can’t just give up, even if a better reality will never arrive.

On Sunday mornings in Tel Aviv, Gil and I would often wake up to the sound of gospel songs coming from an old storage room above the supermarket next door, which refugees from South Sudan rented to serve as an improvised evangelical church. Displaced by civil war, they had fled to Israel and now survived on the margins of a society that made no room for them. One morning, curious about the sounds that floated from the barred windows, I snuck up the grimy staircase to peek in. They stood there, women in colorful dresses and men wearing black suits in the sweltering heat, swaying to the music. With their eyes closed, they reached their arms towards heaven calling on Jesus for salvation, yearning for Zion, even in Zion.

I remembered those refugees as I spun the prayer wheels inside that dark chapel on the Tibetan plateau. I thought of the war, of the panicked last text messages from people about to be killed, and a video of a woman in Gaza screaming from beneath the rubble of a collapsed building: “Help me! Get me out of here! Please! Hurry up! Help me! I’m dying!”

My face wet with tears, I lingered in the comfort of the temple’s shadows, going around and around, passing the other pilgrims as we switched from wheel to wheel, spinning and spinning.