In April 2024, a friend passed me a package. He had received it from someone who attended a debate I had with an Israeli academic in Taiwan, and that person gave him the booklet. I was living in Taiwan, four months past my mother’s death in Khan Younis. The package contained a booklet — stories, children’s drawings, poetry. All of it created in Gaza. All of it sent by email by people still inside Gaza, still under bombardment, still figuring out how to live. The friend of a friend had printed it out and passed it along.

I held it carefully. I didn’t read it right away. I wasn’t sure what I was supposed to do with it.

In October of 2025 a ceasefire began — fragile, contested, possibly temporary. It’s the second extended pause in active bombing since October 7, 2023. As if to underscore the fragility of this calm on October 28th, less than three weeks after the ceasefire began, Israel launched a new wave of bombing across Gaza, killing at least 120 Palestinians. Netanyahu ordered what he called “powerful, immediate strikes.” The sense of fragility I just mentioned — the knowledge that violence could resume at any moment — has justified itself. The ceasefire did not hold. The bombs returned. And while the dust settles in the wake of that rupture, people are beginning to move back into northern Gaza, though vast areas remain uninhabitable. Hospitals are slowly reopening with minimal equipment. Schools are attempting to restart without buildings. There is still no electricity in most places. There is still no clean water for much of the population. The estimates are that 70 percent of structures in Gaza have been damaged or destroyed.

But the daily fear of immediate death has, for many, shifted to a different kind of fear: the fear that the bombs will start yet again. The fear that this pause is not an ending but an interlude. The fear that we’ll return to October 2023 and be surprised all over again by the violence that was always predictable, as though we hadn’t just lived through it. That’s the peculiar terror of ceasefire in Gaza — not the absence of violence, but the fragility of that absence. The knowledge that it could resume at any moment. The constant vigilance required to maintain the belief that it might not.

I no longer have the booklet. I lost it somewhere in the moves between places, between jobs, between versions of myself that seemed necessary after my mother died. But I remember holding it. And now, in this ceasefire time, in this strange liminal moment where Gaza is no longer under active bombardment but no longer at peace either, I’m thinking about what it meant to receive that package. What it means to have received testimony from people inside catastrophe. What we’re supposed to do with that testimony now that the acute phase has paused but the underlying conditions that produced the catastrophe remain largely unchanged.

This is a different ethical problem than the one we faced during the bombing.

When your mother is killed, when the bombs are falling daily, when people are dying in such numbers that the statistics become almost incomprehensible — there’s a kind of urgency to bearing witness. You read the testimony and you think: this is happening right now. This person is writing these words while living under siege. That immediacy creates a demand. Do something. Say something. Make sure the world knows. The testimony demands action in real time. It demands response. It demands that we do something with what we’re receiving.

And now? But what happens when the bombing pauses? What happens when the testimony was created in the middle of the violence, but you’re reading it now, months later, in a time of ceasefire? The urgency shifts. The meaning changes. The question is no longer “what do I do about what is happening right now?” but rather “what do I do with what has already happened? How do I carry forward the knowledge of what people created when everything was being destroyed?”

These are not identical ethical imperatives, and they demand different kinds of responses from us.

I received that booklet in April 2024, in a moment when I was still raw. My mother had been dead for four months. I was still learning how to function without her. I was still figuring out what it meant to be alive when she was not. The grief was not yet integrated into my life — it was still something that would hit me unexpectedly, in the middle of a conversation, in the middle of a lecture, in the middle of an ordinary day. I would be explaining something in English to my students, or reading an essay about political systems, or eating lunch, and suddenly I would remember: she is dead. And the knowledge would arrive fresh on every such occasion, as though I was learning it again for the first time.

The booklet arrived during one of these periods. My friend passed it to me because he understood something important: I needed to know that I wasn’t alone in this knowledge. That there were others in Gaza, still there, still creating, still insisting on meaning-making in the midst of catastrophe. He passed this testimony to me. Evidence. Proof that even under siege, people were still making things.

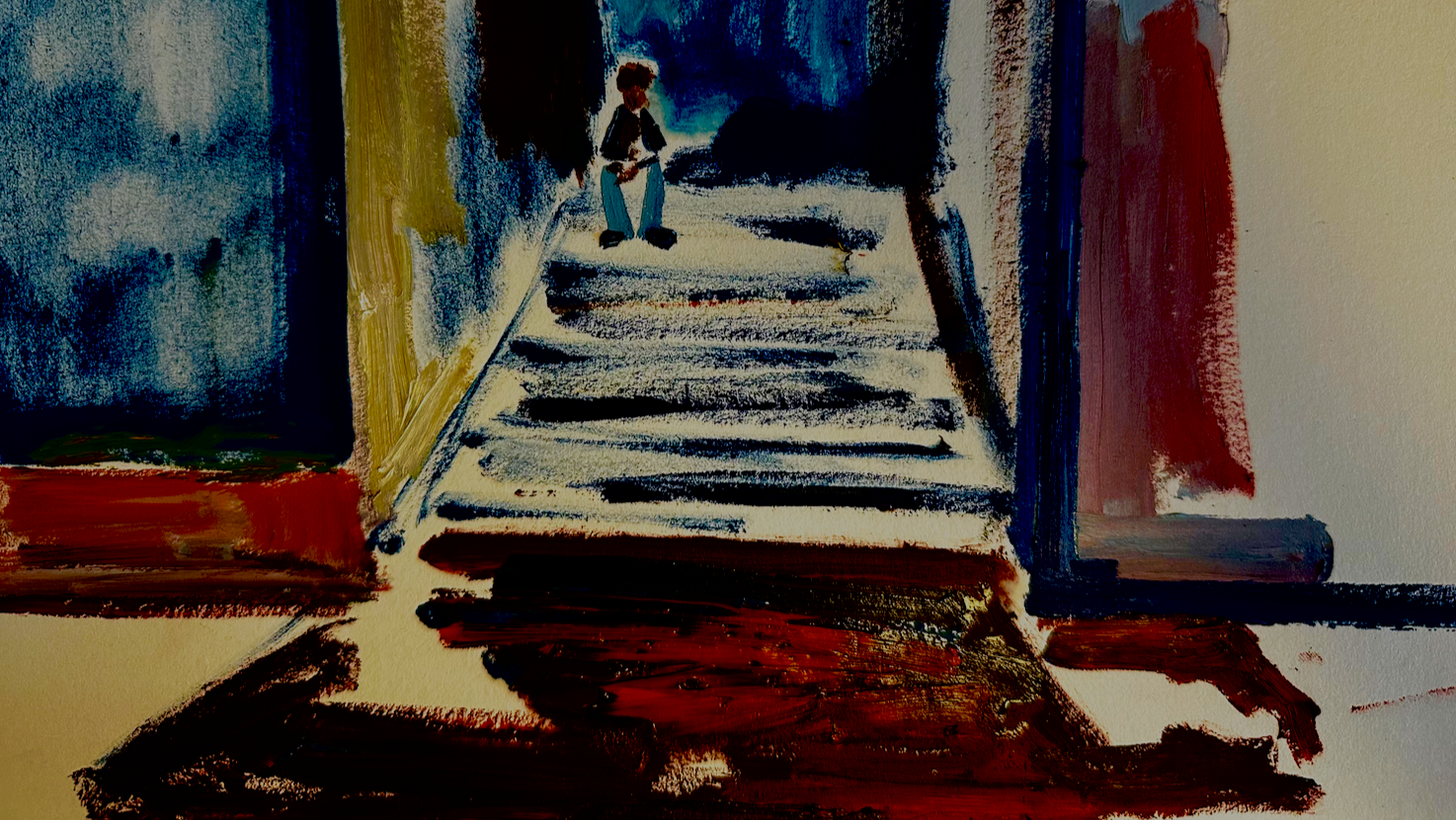

I remember seeing children’s drawings in it. I don’t remember the specific images — my memory is not precise enough to hold those details now, months after I’ve lost the physical object. But I remember the fact of them. Children in Gaza had drawn pictures. They had used whatever materials were available — pencil, paper, whatever they could find in a territory under total siege — and they had drawn. They had made marks on surfaces. They had created images. That act of creation, in the midst of everything, struck me as both unbearably sad and somehow defiant.

What does it mean that children were drawing while dying? What does it mean that they chose to make images instead of just trying to survive? What does it mean that their drawings were being sent via email out of Gaza, to be collected in a booklet, to be distributed to people like me?

What was I supposed to do with that knowledge? With the testimony of children’s drawings made under bombardment? Was I supposed to cry? Was I supposed to be inspired by their resilience? Was I supposed to use those drawings as evidence in a political argument? Was I supposed to share them widely to raise awareness? Was I supposed to let them sit with me quietly, without trying to extract meaning from them?

I didn’t know then. I still don’t entirely know.

But here’s what I think I understand now, in this ceasefire time: holding onto that testimony is itself a form of responsibility. Not reading it, not consuming it, not using it to make a political argument — but literally carrying it forward. Maintaining it. Refusing to let it disappear into history or forgetting or the vast accumulation of atrocities that the world has learned to ignore.

Because that’s what happens after catastrophe. The world moves on. The news cycle moves on. The attention shifts to the next crisis, the next conflict, the next source of outrage. And the testimony from the previous catastrophe starts to fade. It becomes history. It becomes past. People who experienced it are expected to move on, to rebuild, to not keep talking about what happened. The pressure is enormous. You’re supposed to put it behind you. You’re supposed to heal. You’re supposed to find meaning in it and move forward.

This pressure intensifies during ceasefire. Because now the violence has paused, people assume the crisis is over. They assume it’s time to move on. They assume we should be talking about reconstruction, not about what happened before. There’s a desire — sometimes conscious, sometimes not — to let the past stay in the past. To not keep excavating the wounds. To allow people to begin healing without constantly being asked to relive the trauma through testimony.

I understand this impulse. But I think it’s dangerous. Because if people stop bearing witness while the ceasefire is still fragile, while the underlying conditions that produced the genocide remain in place, then we risk returning to October 2023 without having ever truly accounted for what happened. We risk treating the genocide as an aberration rather than as a logical outcome of long-term policies of occupation and siege. We risk allowing the narrative to be rewritten by those in power.

But the testimony doesn’t actually disappear. It lives in the people who received it. In those of us who held the booklet, read the words, saw the drawings. We become custodians of that evidence. We become the living archives of what people created during the genocide. We become the ones who have to remember, so that the story doesn’t become only what the powerful want it to be.

This is a strange responsibility. And I’m not sure we take it seriously enough.

When I think about what I’m supposed to do with the knowledge of that booklet — now that I no longer have the physical object, now that the active bombing has paused, now that time has rolled mercilessly on — I think the answer is: remember it. Bear witness to the fact that it existed. Testify that people in Gaza created art, poetry, stories during the genocide. That they didn’t just survive. They created. They made meaning. They insisted on beauty and language and connection even when everything was being destroyed.

That matters. Not because it justifies what happened — nothing justifies what happened. The creation of art does not redeem genocide. The fact that children drew pictures does not make the bombardment acceptable. I need to be clear about this. There is no redemptive narrative here. There is only the stubborn insistence that even under the worst conditions, people are more than what is being done to them.

I carry that forward now. Even without the physical booklet, I carry the knowledge that it existed. That my friend sent it to me because she understood that I needed to know that people were still creating in Gaza. That creativity continued. That meaning-making persisted. That in the midst of the death and destruction and bombardment, someone was sitting down and writing a poem. Someone was teaching a child to draw. Someone was collecting these creations and sending them out into the world, saying: we were here. We are here. We made this.

What does the ceasefire change about this? Everything and nothing.

The ceasefire means the immediate danger has, for now, paused. It means children in Gaza might be able to draw without worrying that tonight might bring another bombardment. It means people might be able to sleep without listening for the sound of drones. It means life, in some basic sense, might become slightly more possible. It means people can begin the impossible work of counting the dead and identifying the bodies and burying their family members properly, rather than in mass graves, rather than under rubble. It means they can begin to grieve without the grief being interrupted by new violence.

But the ceasefire does not erase what was created during the bombing. The poems written during siege remain poems written during siege. The drawings made by children under bombardment remain drawings made under bombardment. The testimony is not diminished by the fact that the acute violence has paused. If anything, it becomes more precious — not because it’s rare, but because it’s true. It’s evidence of what happened. It’s a record. It’s a refusal to let what happened disappear.

I think about the children who drew those pictures in April 2024. Where are they now? Are they still alive? Did the ceasefire reach them before they were killed? Are they able to draw without fear now, or are they living in the fragile state of those who know that the bombs might start again at any moment? I don’t know. I can’t know. But I carry forward the knowledge that they drew. That they made marks on paper. That they created something during a time when creation seemed impossible. That their drawings were deemed important enough to collect and send out of Gaza, to preserve, to share.

That’s the responsibility I think we inherit when we receive testimony from people in catastrophe. We inherit the obligation to remember not just that catastrophe happened, but that people responded to it. That they created. That they made meaning. That they insisted on their own humanity even as that humanity was being systematically attacked.

The booklet is gone from my hands. But it’s not gone from my memory. And memory, in this ceasefire time, feels like the only appropriate place to keep it. Not to consume it, not to use it, not to put it in a museum or an archive or a historical record—but to hold it. To maintain it. To testify to its existence.

Because what we risk, once the acute violence pauses, is that we’ll treat the testimony as though it belongs to the past. We’ll put it in libraries and historical records. We’ll make it official. We’ll make it history. And in doing that, we might lose something essential about it—the fact that it was created by living people, for living reasons, in the middle of unbearable circumstances. We might forget that these were not historical figures but people still alive, still creating, still hoping for a future where such creation wouldn’t require such courage.

I want to resist that. I want to treat the testimony—the booklet with its stories and drawings and poems—not as a historical artifact but as an ongoing claim on the living. It’s a claim that says: this happened. These people created while being destroyed. You have received this knowledge. You must carry it forward. You must not forget. You must not allow it to fade into the comfortable distance of history.

So I carry it. Into October 2025. Into the ceasefire. Into whatever comes next. Whether the ceasefire holds or whether the bombs resume, whether Gaza is allowed to rebuild or whether it remains a place of fragile suffering, I carry forward the knowledge that people in Gaza refused to be reduced to their suffering. They created. They made art. They insisted on meaning.

And I testify to that. Not to make anyone feel better about it. Not to inspire anyone with their resilience. Not to create a feel-good narrative about the human spirit’s capacity to endure. But simply to say: this is what human beings are capable of. Even when everything is being taken from them. Even when the bombs are falling. Even when the future is uncertain. Even then, they created. They made meaning. They refused erasure.

That deserves to be remembered. That deserves to be carried forward. Not as inspiration, but as evidence. Evidence that people are more complex, more resilient, more creative than the violence done to them. Evidence that they did not wait for permission to create. They did not wait for safety. They did not wait for the bombs to stop. They created anyway. They made marks on paper. They wrote poems. They told stories.

That’s what I carry from the booklet now. Not the specific images or words — those are lost to me. But the fact of it. The knowledge that it happened. The testimony that people in Gaza, during one of the most intense bombardments in modern history, sat down and created. That my friend thought it important enough to collect those creations and send them to me. That I received them and was changed by them.

That deserves to be maintained. That deserves to be testified to. That deserves a place in memory that isn’t diminished by ceasefire or time or the world’s forgetting.