Alfred Dreyfus is having a moment.

This summer, French President Emmanuel Macron declared July twelfth a day of national commemoration for Dreyfus, a Jewish army captain whom a French military tribunal — in a notorious act of antisemitism — convicted of spying for Germany. Originally convicted in 1894, Dreyfus spent five years in a hellish prison on Devil’s Island in French Guiana off the coast of South America before he was pardoned by France’s president in 1899. For years, several French generals, not wanting to admit they were wrong, kept insisting Dreyfus was a traitor, even though there was convincing evidence by 1896 that the actual spy was Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy, a French army officer. Dreyfus wasn’t completely cleared until 1906, when he was awarded the French Medal of Honor. The scandal ripped through French society — hardly a single figure of any significant social, political, or intellectual standing absented themselves from the debate.

Macron is restoring Dreyfus to the forefront of French discourse in part because he wants to strengthen democracy and take a stand against the living, breathing descendants of Dreyfus’ tormenters. As Macron put it, he is declaring a day in memory of Dreyfus to mark “the victory of justice and the truth against hatred and antisemitism.” The commemoration will begin in 2026, the 120th anniversary of the date that France’s highest court declared Dreyfus’ innocence.

The time is ripe: forces of the far right are once again poised to take over in the upcoming French presidential race. Polls show that in the next presidential election, scheduled for 2027, Marine Le Pen’s far-right National Rally Party has a good chance of winning, as it has been threatening to do for some time now. True, Macron won re-election in 2022 with more than 58% of the vote; Le Pen won only 41% that year. But since then, in more recent elections to the European Parliament, the Socialists and the Greens and a social democratic grouping made a strategic decision to vote with the hard left to ensure that Le Pen would not be victorious and indeed, their strategy paid off. But, despite all of this maneuvering, the strength of the French far right keeps building.

Macron’s declaration of a Dreyfus Day comes on the heels of several other parliamentary gestures toward the Jewish martyr. In June, former French Prime Minister Gabriel Attal — himself of Jewish Tunisian ancestry, and leader of President Emmanuel Macron’s centrist Renaissance Party — put forward a motion to award Dreyfus the title of Brigadier General, which was denied Dreyfus in his lifetime. This title would reflect contrition for the years lost when Dreyfus languished in prison. France’s lower house, the Assemblée Nationale, unanimously approved the legislation. All 197 deputies who were present voted in favor. For the promotion to take effect, the French Senate must also now approve it.

Also in recent years, prominent French figures from the centrist-right to the left have called for moving Dreyfus’ coffin from his family gravesite at Montparnasse Cemetery, where he rests among literary, artistic and political icons, to the Pantheon, final resting place for many of France’s most revered public figures. When I visited Dreyfus’ grave in Montparnasse this past July it was framed in a gaggle of memorial stones, probably more stones than any other grave I passed in the vast cemetery. The graveyard includes members of Dreyfus’ family and a written memorial to his granddaughter Madeline, who died as an anti-Nazi resistance fighter transported to Auschwitz.

In concert with this effort to express solidarity with Dreyfus and all he has come to symbolize, a timely major exhibition about Dreyfus is on display through the summer at the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire du Judaïsme in Paris’ trendy Marais district. Yet gaining entry to the exhibit reminds visitors about how precariously French Jews have come to regard their own safety. A guard lingers on the street outside the museum to ask why you are entering. If satisfied with your answer, he escorts you to a door with a double-locked entrance chamber. One door must be shut before the other opens, and the visitor must slip through the middle like a security sandwich.

The museum is in the Marais because that neighborhood area was once a center of Jewish life, first for Jews from Alsace-Lorraine (Dreyfus among them) and later Jews from Algeria and other countries in North Africa, as well as Jews from Eastern Europe who fled pogroms towards the end of the nineteenth century. Today, there are several falafel restaurants and a kosher sandwich shop, but not much else to remind visitors of its Jewish history. The area itself has become a trendy open-air mall with boutiques and chain stores — there is even a Krispy Kreme Donut shop on the Rue des Rosiers, long the heart of the Jewish Marais. Dreyfus, meanwhile, would never have lived in that part of town. He strove to situate himself among the upper class, never in the tiny, often grubby side streets of this part of Paris.

The Dreyfus exhibition includes 250 archival documents, photographs, newspaper front pages, film extracts, cartoons and artwork by Gustave Caillebotte, Camille Pissarro, Félix Vallotton, Édouard Vuillard and others underscoring the cultural significance that the Dreyfus Affair achieved in French society. The antisemitic caricatures pile one on top of the other on the exhibit walls to convey how this case unleashed an antisemitism that permeated all of French society.

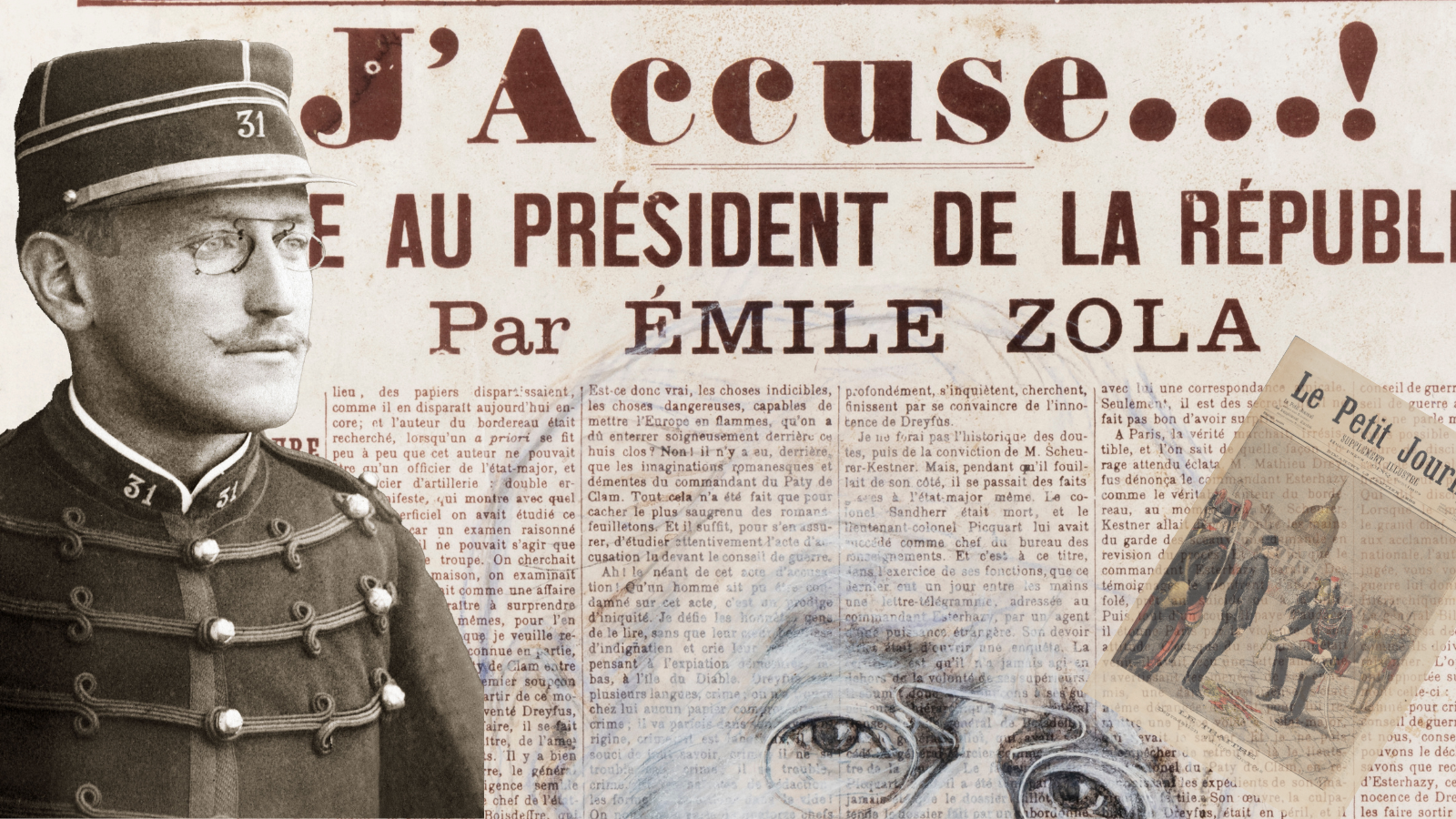

And there was a backlash to the bigotry, also on display in the museum. Included in the show is a copy of Emile Zola’s famous “J’Accuse,” an open letter to the French President that detailed the conspiracy that framed Dreyfus. Zola’s 1898 letter appeared in the newspaper L’Aurore as a challenge to the French establishment for allowing and abetting this shameful incident. Zola’s courage came at a price. After publishing it, he had to flee to England to escape prosecution for his accusations against the state. But Zola’s pronouncement did the trick. L’Aurore ran the manifesto in a special edition with a 300,000 print run. Leon Blum, a Jew who went on to become France’s Socialist Prime Minister as head of a Popular Left Front just before World War II, wrote that “J’Accuse turned Paris on its head in a single day.”

The power of the Dreyfus example is communicated most effectively through careful storytelling. The exhibition’s most striking element was not in its galleries, but in the gift shop. That’s where the huge number of books about Dreyfus on sale make clear how the Dreyfus Affair continues to burn more than a century later. There are several tables of books about Dreyfus, including Proust’s and Zola’s fiction — both were staunch Dreyfus supporters.

Indeed, anyone determined enough to read through the seven volumes of In Search of Lost Time will see for themselves how much the Dreyfus Affair reverberated through the high French society which Proust conjures in that great work. The books take place at the same time as the scandal rattled Paris. Proust’s characters are divided neatly between pro- and anti-Dreyfusards, with Proust — himself an assimilated French Jew — resolutely on the side of the Dreyfusard Republicans, defenders of a liberal state. The ballroom scenes that fatten these volumes are replete with meditations by Proust’s nameless narrator regarding who aligns with whom in the room, based solely on their positions regarding Dreyfus’ guilt or innocence.

Marcel, Proust’s narrator, is obsessed with Dreyfus. Worried about Swann’s waning health, deep into the fourth volume of the series, the narrator inquires and gets this response: “I confess it would be very irritating to die before the end of the Dreyfus Affair. Those scum have more than one trick up their sleeve. I don’t doubt they’ll be beaten in the end, but they’re very influential, they’ve got support everywhere. Just when it’s going best, everything gives way. I’d like to live long enough to see Dreyfus rehabilitated and Picquart a colonel.” (Picquart was another French officer, not Jewish, but also condemned with Dreyfus for being part of the conspiracy).

The exhibition concludes by shifting in a direction that Dreyfus himself would not have sanctioned. The final installments before the exit depict and detail the First Zionist Congress, implying that departure from Paris to Palestine is the only reliable salvation from European antisemitism. Dreyfus was emphatically not a Zionist. He never denied his Judaism, but he was always determined to be wholly a part of French society, whether French society wanted him or not.

In fact, and somewhat ironically, his family tried to play down his Judaism throughout the ordeal. The Dreyfus family did all they could to distance themselves from prominent Jews denouncing the slander for what it was: an antisemitic libel. They shimmied far from the Jewish intellectual and leftist Bernard Lazare as he railed against the clear anti-Jewish bias that placed Dreyfus in chains. (Lazare’s book, Antisemitism: Its History and Causes, was published in 1894 and was the first systematic study of antisemitism.) The Dreyfuses chose instead to encourage prominent non-Jewish intellectuals like Emile Zola to take a lead in the defense.

Even Jewish supporters like Lazare believed that anti-Semitism would disappear as capitalism gave way to a global socialism, a utopian vision that, of course, never came to fruition. Dreyfus himself resisted the Jewish and Zionist connection, but his own life overlapped with the creation of the Zionist Movement that was born in the late 1800s, and he could do nothing to temper the effect that his own trial had on Jewish Frenchman who watched the antisemitism swirl in French society and drew their own conclusions. Indeed, what became known as Dreyfusism, the dangerous attack on a prominent personality solely because of his Jewishness, clarified for many who followed Dreyfus that Zionism was essential to Jewish survival. Theodore Herzl himself, the father of modern Zionism, was a journalist at the time the case made headlines around the world and he later claimed that the Dreyfus case deepened his faith in the necessity of Zionism.

And, of course, there are the events that followed decades later. Vichy France and the Holocaust seemed to repudiate Dreyfus’ beliefs that Jews could melt into the French fabric. And so did the role of the Catholic Church, a major culprit in Dreyfus’ shaming and slander. Hannah Arendt wrote that the “only visible result” of the Dreyfus Affair was “that it gave birth to the Zionist movement.”

Yet Dreyfus’ case has also become a Rorschach test for democracy itself and a warning about the dangers of populism and the intractability of ethnic hatreds. In fact, New York City’s Film Forum just announced a two-week run this August of Roman Polanski’s drama An Officer and a Spy, a fictionalization of the Dreyfus story based on the novel by Robert Harris. (The film has not appeared in the U.S. since its 2019 debut at the Venice Film Festival after Polanski pled guilty to the statutory rape of a thirteen-year-old child.) FilmForum writes on its website that the film is important to show now because it is “a well-crafted, dramatic depiction of the Dreyfus Affair — a landmark case of institutional corruption, antisemitism, and resistance to both, and a timely reminder of the perils of being a whistleblower.”

Democracies on both sides of the ocean are both looking back to the Dreyfus case as an instructive and forbidding foreshadow of the evils which stalk us today. Two hundred years later, we still have much to learn from that example.