“What were you working on?”

This is asked of every actor after any scene or monologue or acting exercise done at the Actors Studio sessions held twice a week in the old church on 432 West 44th Street, the Studio’s location since 1955. Two projects are presented each session. The members gather in the drafty big room to watch. Someone moderates – Estelle Parsons, or Harvey Keitel, or Ellen Burstyn.

Marilyn Monroe poses outside the Actors Studio in 1955. Photo: Radio TV Mirror Magazine. Wikimedia Commons.

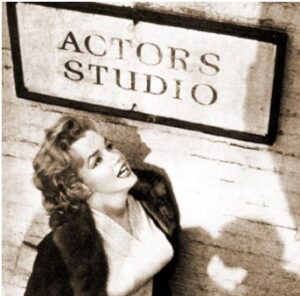

actors studio attendance sheet featuring Paul Newman, Jack Lord and Marilyn Monroe – April 29, 1955 – Manuscript Division. Library of Congress.

The sessions are not about presenting a finished product. They aren’t rehearsals. You can work on just one element of a scene if you want. For example, you can work on Brick in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and only focus on the character’s drunkenness. You can do an improvisation to explore the text. The question asked by the moderator — “What were you working on?” — is the starting point of all discussion. Ideally, the comments given by the group should be focused on whether or not the actor accomplished “what they were working on.”

Asking “What were you working on?” avoids the usual unhelpful commentary in acting classes, such as “That was good/bad.” “What are you working on?” allows the actor to take ownership of their process, as well as fine-tune the perceptions of the watchers. Was the actor working truthfully? Did they get in their own way? Did they gain something from the exploration?

I love the question. “What were you working on?” destabilizes the hierarchy. It places everyone on the same level. A good question is not a judgment. It has no ulterior motives. We want to hear the answer.

In Act II, scene 2 of Hamlet, Hamlet watches the traveling acting troupe rehearse and, famously, notes that one of the actors evinces more passion for the fictional situation than he, Hamlet, has shown in avenging his father’s death:

Is it monstrous that this player here,

But in a fiction, in a dream of passion,

Could force his soul so to his own conceit

That from her working all his visage wann’d,

Tears in his eyes, distraction in ‘s aspect

A broken voice, and his whole function suiting

With forms to his conceit? And all for nothing!

For Hecuba!

What’s Hecuba to him or he to Hecuba,

That he should weep for her? What would he do,

Had he the motive and the cue for passion

That I have? He would drown the stage with tears.

The rooms in the Actors Studio are, as you can imagine, intense ones. I live for intense rooms. In those charged spaces people routinely tiptoe out onto a limb in front of an audience, publicly attempting to enter the “dream of passion.”

The Dream of Passion, Parts 1 and 2

I have been writing professional film criticism since 2010, when I got my first paying gig. Before that I wrote mainly on the blog I set up in 2002. However, if you add up the years of my life, the hours spent in rehearsal spaces, script in hand, far outnumber the hours spent in screening rooms, scribbling my thoughts in a notebook. Acting was the first dream. Writing about film was something else. I didn’t let go of one dream and take on another. The second activity felt like an extension of the first, although I wouldn’t have put it that way when I started.

I didn’t have to flail around as a child wondering what I wanted to do with my life. My aunt Regina is an actress. Going to see her in plays was a huge influence on how I saw the world. A family member did this thing as a regular job. There wasn’t a mystique about acting careers. All you had to do was work hard.

As a kid I absorbed movies and television, much of which were not appropriate for my age, in keeping with the un-monitored viewing habits of a Gen-X child. I saw East of Eden and Dog Day Afternoon at around age thirteen; they happened to be on television when I was babysitting. I had never seen anything like James Dean or Al Pacino before in my life. I could barely understand what I was watching, I did not know who they were — I didn’t know James Dean was a figure from the past, he was “right now” as far as I was concerned.

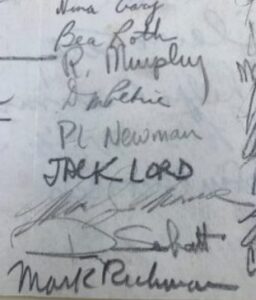

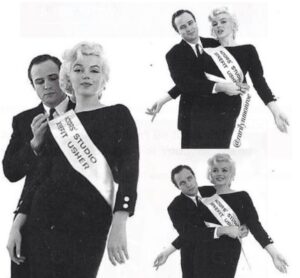

Marlon Brando and Marilyn Monroe in publicity for the Actors Studio benefit screening of “The Rose Tattoo” 1955.

I majored in theater in college, went to grad school for acting, and then moved to Chicago where, for a number of years, I worked all the time. I didn’t know it then, but I was living the dream. Every rehearsal process was different, every project required something new. I studied with incredible people — including Actors Studio luminaries such as Ellen Burstyn, John Strasberg, and Sam Schacht. Their world had been my world since childhood. Acting isn’t just my background. It is me.

“Blogs” were a new phenomenon in 2002. I set mine up on a whim. I had no plan. I discovered there was a passionate readership for six-thousand word essays on, say, a gesture Cary Grant made in a screwball comedy eighty years ago. The actor-things obsessing me obsessed others. In retrospect I see that all this was a way to manage the grief over my first dream not coming to pass. You could say I gave up too early and you wouldn’t be wrong. It’s not fashionable to admit, but I was lost for a very long time. Years. There were other factors at play, mental factors of which I was barely conscious. Sometimes it was all I could do to make it through the day. Writing about actors made me feel connected to the source, the shimmering ever-changing art of playing make-believe on purpose.

I entered the world of film bloggers, a rich varied place in the mid-2000s, before social media scattered small eccentric communities. Blogging back then was like living in a neighborhood where every morning you’d go out for a walk and visit each house to see what your neighbor was talking about. I learned a lot from reading other people and absorbing their expertise. In studying acting rather than film, there were a lot of gaps in my knowledge — vernaculars and points of reference I lacked and which other writers taught me. In my first brushes with the blogging-world, I encountered a lot of wholly unfamiliar attitudes. The creative process seemed somewhat mysterious to a lot of these writers. The “auteur theory” was new to me, and in its most stringent application there was almost no relation to my experience on the ground.

The auteur theory is generally thought to have “started” with the editors and writers of the Cahiers du cinéma, but they didn’t invent the concept. They were just the ones who made it an organizing principle. The theater auteur has a long history, a history I knew a lot about, and it’s how I contextualized what I learned. The ballet impresario Serge Diaghilev, founder of the Ballets Russes, referred to his dance troupe as “cattle,” and brought together every aspect of a production — design, costumes, choreography — into a mesmerizing spectacle. The result was unmistakably his. He was a dictator: It was Diaghilev’s world and his collaborators were just living in it. Konstantin Stanislavski, co-founder of the Moscow Art Theatre, doesn’t have Diaghilev’s martinet reputation, but he brought a passionate focus to what he created. He wanted a theater grounded in realism. In order to achieve that, he needed collaborators who were willing to work in new radical ways. Martha Graham created dance pieces that were so “hers” they could not be imitated, and her style is still recognizable from five miles away. Peter Brook, who died in 2022 at the age of 97, was another singular artist — so singular that his famous circus-themed production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1970, is often referred to as “Peter Brook’s Dream.” Now that’s an auteur.

But there was something about the way “auteurism” was discussed in the film world that struck me as confused, or at least incomplete. The director was so prioritized and given so much credit I wondered where “collaboration” was in all of this. A critic giving a director credit for an actor’s performance, for example, is very common. And it’s wrong. Most directors say casting is ninety percent of their job. Directors know they aren’t “in charge” of the performances. John Cassavetes didn’t take credit for his wife Gena Rowlands’ performances in the films they made together. Rowlands was her own auteur. Elia Kazan said the main challenge in working with Brando was to stay out of his way. Brando’s impulses were so fine-tuned, so intuitive, Kazan didn’t want to screw it up.

By some magnetic force in the blogging world, actor-focused writers became aware of each other. You got to know the people who came from a base of understanding, who didn’t describe performances with a series of adjectives, but dug into the how and why. An incomplete list of colleagues who write perceptively about performance: Dan Callahan, Farran Smith Nehme, Stephanie Zacharek, Angelica Jade Bastien, Kim Morgan, Glenn Kenny, Charles Taylor. I learn from these people. They help me see better.

If you haven’t tried to act yourself, it might seem like it happens by magic. Hamlet wonders how a fictional situation can elicit real tears from an actor. A lot of the confusion about acting that I see in some of the commentary could be cleared up in one afternoon by attending a rehearsal for a community theater production of Our Town or The Crucible or … it doesn’t matter. What you will see is a bunch of people in a room, problem-solving, solution-finding, trying stuff, creating together. The same thing happens in film. The budgets are bigger, that’s all.

The Question, Part 2

As I started writing film reviews, as opposed to long essays about Cary Grant’s gestures, I experienced new challenges. If auteur-theory writers were focused mostly on directors, I was focused mainly on actors. This has pros and cons. If you follow only directors, you’ll miss a lot. If the director isn’t considered an “auteur,” he isn’t prioritized in the “discourse.” Worthy movies fall through the cracks. On the flip side, if you follow actors’ paths, you’ll miss a lot of films in the so-called canon. There needs to be a balance, but more than balance, what is necessary is curiosity. Be as open as an actor on the first day of rehearsal, figuring out their “way in” to the script. Don’t make up your mind before it’s time.

I come back again and again to the first question.

I sit in screening rooms asking the film: “What are you working on?” Different films try to do different things. Be open to what it’s attempting, I tell myself, even if it misses the mark. Asking “What are you working on?” also helps when the film is maybe not made “for me.” If a film is pitched at 14-year-old girls then a middle-aged man might not like it or “relate.” But personal preference is irrelevant. Not everything is for you. The Twilight franchise was dismissed and mocked by the critics who found it silly and stupid, or commentators who worried the “message” was dangerous. Both groups completely missed the obvious: whatever the franchise’s stylistic or thematic faults, it tapped into a generation’s motherlode of passion and yearning in a way few films do. Twilight also launched two of the most interesting acting careers in recent memory, which would have seemed absurd back in the height of Twilight mania. Some expressed surprise when Kristen Stewart and Robert Pattinson were “good” in later projects or that they worked with great directors like Olivier Assayas, Kelly Reichardt, David Cronenberg, James Gray, and Claire Denis. There should have been no surprise. The teenage girls already told you they were good. You just didn’t listen.

What’s Hecuba to him or he to Hecuba,

That he should weep for her?

That is the question.

“What were you working on?” leaves space for the answer, leaves space for the dream.