As a child in the Connecticut suburbs, John Margolies was fascinated by “the ugliest stuff in the world.” Coffee pots, pink flamingos, candlepin bowling, he liked a mess. Later, as an architecture critic and Warhol factory layabout — he briefly appeared in Warhol’s film Camp — that childhood fixation informed his professional eye: Margolies spurned the sleek minimalism of high modernism and became an advocate for the lowbrow, especially the kind of thing you used to be able to find by the side of the road, like a plaster and plastic donkey the size of a cow barn.

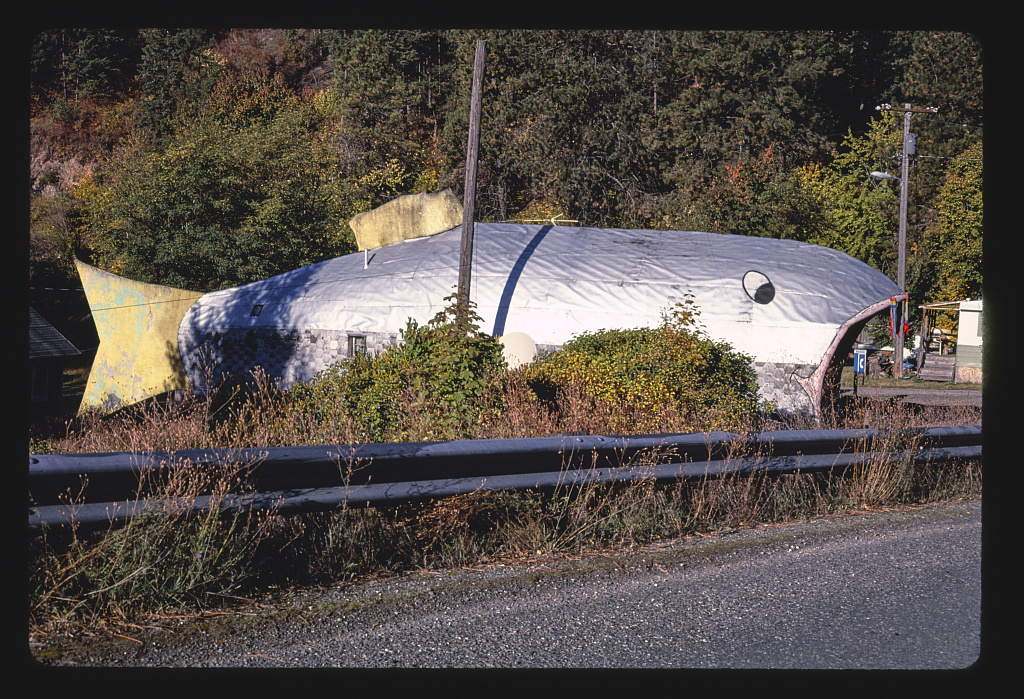

In the early 1970s, as suburbs replaced farmland and the interstate drove people off state roads, Margolies began to worry about the homogenization of the American landscape. Great swaths of American Art Brut were disappearing. No one seemed to value the junk enough to register its obliteration. He decided to chronicle the loss.

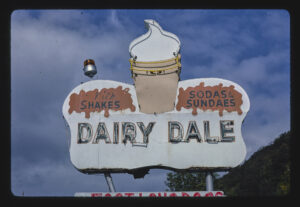

Skimming through the photos is like wandering around a continent-wide boardwalk. But in the half century since Margolies took these pictures, consolidation and ruthlessness have narrowed the planks. The places Margolies photographed have mostly disappeared, absorbed into the few dozen dominant, inescapable chains: the Shell sign, the Starbucks siren, the colonial cupolas atop every Cumberland Farms mini-mart. Take the modern Dairy Queen which was once just one member of the Dairy royal family: we had a Dairy King, a Dairy Princess, and, the black sheep I imagine, a Dairy Dale. Photographed in Margolies’ distinct blue-sky style, the Dairy Dale sign, with its crooked wire letters, is an ice cream cone emerging from a cloud, flanked by two scoops of fallen chocolate promising “rich shakes” and “sodas & sundaes,” respectively. Many of the stores conjure a unique blend of American exceptionalism and American kitsch; there is no other country where you could drive past an igloo ice cream palace. And why drive past it? Looking at these pictures, you become a child tuned out in the backseat, puzzled at how your parents’ generation left so many great spots at the wayside. Perhaps a lack of critical appreciation explains the disinterest. Someone must have told the young John Margolies that the stuff he liked was ugly.

Margolies’s blue-sky belief in ordinary people as makers was part of a generational revolt. Margolies, born in 1940, had grown up in the golden age of comic books and the early years of television, saturated by post-war American optimism. His elders had watched the rise of Hitler and Stalin. An older generation of (mostly) Marxist critics had a seething hatred for kitsch. For example, in The Dialectic of Enlightenment, the (refugee) German philosophers Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno described kitsch as emanating from “the total assimilation of culture products into the commodity sphere” combined with the morality of “yesterday’s children’s books.” A leviathan of bad taste which “bows to the vote it itself has rigged” in order to “artfully sanction the demand for trash.” Rough.

Adorno was a major league hater (read him on jazz or astrology) but American-born critics were hardly kinder. In his 1939 essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” the art critic Clement Greenberg put the elitism plainly: “Ersatz culture, kitsch, destined for those who, insensible to the values of genuine culture, are hungry nevertheless for the diversion that only culture of some sort can provide. Kitsch, using for raw material the debased and academicized simulacra of genuine culture, welcomes and cultivates this insensibility.” Sentimental, moralizing, and gaudy, kitsch is the vocabulary of propaganda and advertising, it styled Nazism and Soviet Realism too. But it also is the language of tchotchkes and quilts and bedtime stories.

As political messaging, kitsch is manipulative to the extreme, as a series of watercolors in your uncle’s basement it’s charmingly guileless. A younger less buttoned up set ditched the austere maxims of their predecessors, instead finding the beauty and charm in kitsch art. Susan Sontag, John Waters, David Lynch, all born in the 1930s and 1940s, while not disavowing classical styles, looked closely at the eyesores. As their work became popular, divisions between high and low art relaxed. A flat distinction became parabolic, no longer differentiated by critics but pulled together like a golden arch. Being “insensible to the values of genuine culture” might make you fall asleep at the opera or vote for a crooked DA, but it doesn’t mean you can’t make something great. It also doesn’t preclude you from selling out.

“He had assumed that a man named Howard Johnson made ice creams, an ice-cream scientist, someone with a visionary sweet tooth, a chemist of fruits and candies, a larky alchemist who reduced the tangerine and the mango, the maple and marzipan to their essences, who could, if he wished, divide the favor of the tomato and the sweet potato from themselves, a tinkerer in nature who might reproduce the savor of gold, the taste of cigarette smoke.” So reels the mind of Benny Flesh, the Wharton grad hero of Stanley Elkin’s novel The Franchiser, in 1976, as he learns that anyone with $40,000 can own a Howard Johnson’s. (Elkin was a very serious prose stylist with a streak of demented whimsy. Imagine a sort of elfin Saul Bellow, his Dairy Dale, if you will.) It is a major revelation: Benny remarks in disbelief, “He sells his name?” Today we think of this kind of franchising as normal, at the time it was novel — using a family name implies a degree of care and responsibility. Howard Johnson was originally a real man, using his mother’s ice cream recipe. Why was he willing to certify so many cones? How do we reckon with the adoption of a homegrown aesthetic by big business? At how many customers served, does a scrappy small business become a soulless chain? When do we realize Howard Johnson, ice-cream scientist, is as relevant to his product as Ronald McDonald, hamburger clown, is to a Fillet-o-Fish?

Bargain and Cadillac driving men, like Elkin’s franchiser, also saw value in the nostalgia-inducing aesthetics of the American roadside. Their concern was not preservation but profit, not fighting homogeneity but making sure they were on the winning side. The difficulty in positioning Roadside Americana as art is that it is foremost business. Even the most visionary and outlandish designer would find a corporate offer hard to refuse. There is a world where Captain Bob’s Barbeque Bull can be found in Terminal 4 at the Hong Kong Airport. Any number of humble businesses could have become inescapable franchises: What does it mean if we prefer the ones that didn’t?

The Janus face of elitism is anti-elitism. Just as Adorno and Greenberg happily relegated kitsch to the black pit of bad taste, the French artist Jean Dubuffet elevated Art Brut, arguing that “Works created from solitude and from pure and authentic creative impulses — where the worries of competition, acclaim and social promotion do not interfere — are, because of these very facts, more precious than the productions of professionals.” This definition partially — but usefully — explains the appeal of the many forms of art crafted by those without classical training. Its appeal endures. The art critic Dean Kissick insists — after dubbing Twitter “The most honest portrait of humanity ever made” — that “Ordinary people, it turns out, are far weirder than artists and writers, and more imaginative too.” Are they, though? Roadside Americana is beautiful, but you don’t need to be “more honest” “more human” or “weirder” to do it. The grande dame Joyce Carol Oates can Tweet with the best of them and Louis Kahn, born in 1901, could have made a bang-up burger shack. The Pizza Hut, one of the strangest roadside attractions ever made, was designed in the Americana style by a modernist architect from Chicago. Does knowing that ruin the facade?

A more nuanced view is possible. We don’t have to choose between Adorno’s disdain and Dubuffet’s adulation. The literary critic Sarah Webster Goodwin reconciles the alleged dichotomy: “Kitsch is at the edge of art, unsettling its categories of value and larger cultural meanings, challenging its relation to the marketplace and to its audiences.” The Marxists (and conservative critics too) were correct to point to a certain dumbing down of culture as a negative, but it is also a bit funny to imagine someone disdaining Grandma Moses as a force of mystification. At some point, kitsch moves beyond the dictates of the culture industry. There’s mini golf, the academicized simulacra of genuine golf, and then there’s Sir Goony the Mini Golf Spider, who transcends his circumstances.

Whether Adorno was right and Margolies’ taste for the roadside has, “artfully sanction[ed] the demand for trash” or, as Goodwin hoped, helped in the good quest of “unsettling categories of value,” his enthusiasm was genuine. It certainly transcended any practical relationship it had to his career as a critic. Of the 11,751 photos in the collection, a great many are extraneous to his ostensible project. There are, among other things, sprawling records of trips to Borscht Belt vacation spots (and Margolies’ enthusiasm for the Jersey Shore more than exceeds anthropological or aesthetic curiosity). While many of these oddities, like a series of porch chairs, could have been kept in the family photo binder, others are vibrant and uncanny. His food photography stands out. Margolies shot plates the way he shot buildings: isolated, stark, and always brightly lit. His touch made humble snack bars monumental, and buffet fare ominous. Watermelon Rabbit, served up at the Menges Lakeside in Livingston Manor, New York, is as unappetizing as the forgotten rabbit dinner in Polanski’s Repulsion or the living ones in Lynch’s Inland Empire.

Margolies captured an American roadscape on the eve of its dismantlement, but you get the feeling that the photographic project was secondary to the roadtrip. The huge monoliths, the shimmering signs, the wide-ranging cultural allusions, the gonzo specificity, they drew him in; the critical gesture was just an excuse to take every exit. This was a man who believed in billboards. He wanted to see every local mascot, try every grandmother’s famous apple pie, and stop at every beach with a funny name. He enriched our America by preserving its ghosts. Thousands of the businesses he photographed are permanently closed, many of the monuments are wiped off the map: roadkill.

One of the many milk-fed entrepreneurs who succeeded as artisan and failed as businessman was our forty-fifth president. The Trump Taj Mahal is a roadside piece de résistance. A kitsch replica of the Indo-Islamic architectural masterpiece — a UNESCO world heritage site with the perfect symmetry of a paper flower and which, in its careful balance of the concave and convex, seems to flicker with divinity — was remade as a casino and relocated to the Atlantic City boardwalk. The casino went bankrupt but it failed beautifully. In 2021 the Trump Taj Mahal was demolished by three thousand sticks of dynamite. The casino once called ‘the eighth wonder of the world,’ reduced to rubble in twenty seconds. Whatever happens in November, Trump is forever commander-in-kitsch..

Franchisers like Trump may have won the roadside, but the uncanny eye of American small business remains. The attraction that started Margolies’ mission remains popular and nonpareil. His review puts the appeal nicely: “The Madonna Inn is a living, unfinished monument. Alex and Phyllis Madonna continue to develop the Inn in their own distinctive, untrained way, unscathed by the aesthetic criticism of those who know or think they know. What the Madonnas know is what they like, and they know how to get what they like.”